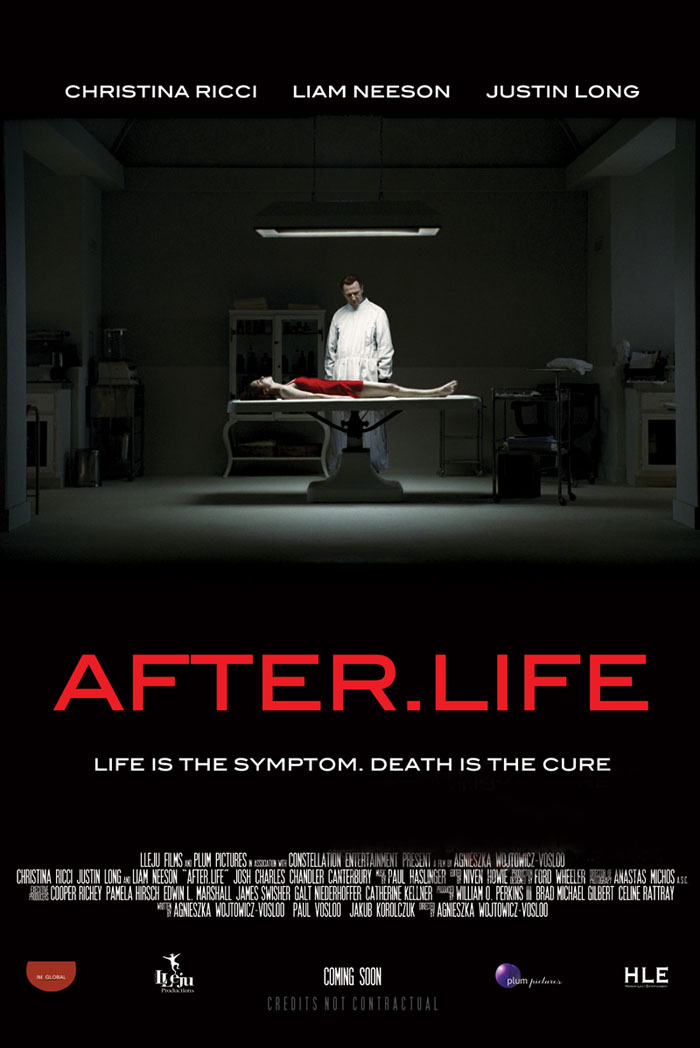

After.Life is a stylish and stunningly-curated new psychological thriller starring Christina Ricci as Anna, a car crash victim who wakes up to find that she's... dead. In a mortuary. Funeral director Eliot Deacon (Liam Neeson) seems to be the only person who can see or hear that she's alive, and he informs her that her soul is trapped and he's going to help her cross over, but her grief-stricken boyfriend Paul (Justin Long) has a growing suspicion that Eliot is not as he seems and sets out to unearth the truth before it's too late. This film is the directorial debut of Agnieszka Wojtowicz-Vosloo, with whom I talk about the movie, the allure of death as a motif, and the way being female can affect a young director's experience in Hollywood. Enjoy.

After.Life is a stylish and stunningly-curated new psychological thriller starring Christina Ricci as Anna, a car crash victim who wakes up to find that she's... dead. In a mortuary. Funeral director Eliot Deacon (Liam Neeson) seems to be the only person who can see or hear that she's alive, and he informs her that her soul is trapped and he's going to help her cross over, but her grief-stricken boyfriend Paul (Justin Long) has a growing suspicion that Eliot is not as he seems and sets out to unearth the truth before it's too late. This film is the directorial debut of Agnieszka Wojtowicz-Vosloo, with whom I talk about the movie, the allure of death as a motif, and the way being female can affect a young director's experience in Hollywood. Enjoy.Hi!

Hi, how are you?

I’m good. How are you?

I’m very well, thanks.

Are you in New York?

I am! I’m at home, actually. Where are you?

I’m at school. [laughs]

Oh, all right! Is it a good school?

Yeah, it’s good, but I’m… ready to go to college.

Oh, okay, you’re at that point. [laughs] Sounds exciting.

[laughs] Well, let’s talk about After.Life.

Absolutely.

How did the idea come to you, and how’d you get started working on the film?

Well, I was always fascinated and terrified by death—since I was a kid, actually. My father died when I was ten, and that was something that left a huge influence on me. Still, at first it was just this image of a young woman in red lying on a slab in a mortuary, and the mortician was basically preparing her body for the funeral, and suddenly this woman opens her eyes and says “Where am I?” and he very calmly says “You’re dead. You’re in a funeral home; your funeral is today.” That was kind of the image I had of this entire story about what happens after you die, and I’ve always wondered whether there was some kind of transitional period where your soul or your consciousness kind of remains with you so that you feel alive when you’re dead.

Well, when you couch the premise in those terms, it sounds like a supernatural version of the sorts of prompts Hitchcock used for his films.

Oh, that’s a huge compliment right there! Thank you! I love Hitchcock; he’s one of the directors I kind of grew up on, really. At the same time, I’m interested myself in… heightened reality. I guess I would put it that way. The stories that fascinate me always start in reality but take on a very surreal, almost heightened, feel, and that’s what I did in my short film Pate, which was about an aristocratic family dealing with the aftermath of the apocalypse—

Yeah, I was actually about to bring up the fact that you also did that in Pate, taking situations that would normally be explorations of characters and then altering the environment to make the situation more heightened.

Uh-huh, that’s exactly it. I like very primal stories, you know, stories that deal with primal fears, primal emotions, and death is obviously not only the last remaining taboo but it’s also a fear we all have. And Pate was similar in that it was a character study of these two people and this relationship between a mother and a child, but I added this post-apocalyptic environment to it, which made it that much more twisted and heightened.

Right. And I know you were a child actress, so that probably influences the way you approach storytelling—especially the actual act of directing.

Absolutely. I tried acting when I was little, and it wasn’t really a career choice; I loved theatre and everything, but it wasn’t a conscious dream, wanting to be an actress. Actually, when I was on set, I enjoyed acting but I also enjoyed waiting, which is something most actors hate, because I could go around to all the departments and…

Just sort of poke around. See how everything worked.

Oh, absolutely! And I was always getting in trouble. I would go to grips and be like “Oh, can I move this piece?” and they’d be like “No, don’t touch it!” And I would go to the costume department, and to makeup, and I loved it. I felt really early on that I was never intimidated by the whole process; the idea of everyone working together and everyone collaborating actually really excited me. And now that I’m on the other side of it I can say that being an actor really helped me because, having been in their place, I can understand what it takes and how much it takes out of an actor to do what they do.

So I don’t know whether you want to talk about this or not, but this is your first movie and you are a female director, and… there are certainly far fewer female directors working than male directors. So I was wondering if you’ve experienced anything differently in the industry because of your gender.

Yeah, I think that’s a very important question, and usually what I experience is a combination of being young and maybe being female but also doing dark material. I’ve never really allowed the idea of “Oh, I’m a female director!” to enter into the equation of what I’m doing because it’s a hard business anyway and it’s a hard job and there’s no reason to make it even harder for yourself; I’m almost not letting myself even think about it. But I definitely do see that surprise when people read my screenplay and then come in to meet with me, like they expected someone much older, or maybe a guy. They definitely are surprised, and especially since my short film was dark and twisted people would say, like, “Oh, you made this film?” as if they were expecting a guy. In terms of working with a crew and working with actors, I’ve never experienced being female as a negative thing, thank god, and I think as a director—whether you’re female or male—you have to earn the respect of your crew and your team and your actors. So that’s kind of normal, and I’ve had an amazing crew and an amazing cast who were extremely supportive. It’s interesting; with Kathryn Bigelow winning the Oscar, everyone’s saying things like “It’s finally the year of the woman!” but I actually think there’s still so much work to be done.

Oh, for sure. I think it’s great that a woman finally did win an Oscar, and not just because she was a woman but because she directed a film that the Academy obviously really liked, which is important, but like you her Oscar makes me worry that people will think we’re done when we’re not. Still, one thing that was important about The Hurt Locker getting so much attention is that I think it will open people’s minds about what female directors are capable of doing.

I mean, it’s an interesting subject to talk about. I have to tell you, I’ve been doing Q&As at various colleges for After.Life: I went to the New School; I went to SVA; I went to NYU, and I screen the movie and then afterwards we have a Q&A. Usually the audience is divided half-half, half-guys and half-females, and the female audience members always ask if it’s harder to be a female director. It’s almost like it’s becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy, you know, there being fewer female directors because of this stereotype that it’s harder. It’s a dangerous stereotype, and I see these young women kind of continuing it, if you know what I mean; they’re almost expecting it to be harder. So I tell them that I never even allowed it to enter my thought process. And, again, with the dark material, I always get asked the same questions, as if women were not capable or allowed to direct psychological thrillers or horrors, and I always say those genres are not just for men. I have dark sensibilities and I love them; I kind of gravitate toward this, and it’s not like women can only direct romantic comedies, you know?

Right. For sure.

At the same time, I think change will come when more women are doing psychological thrillers and horror because then it will become the norm rather than the exception. Like, I’m the exception because I’m doing a horror-thriller, whereas it’s a norm for guys to do that.

Not to mention action films and mysteries, as well, or basically anything that isn’t… for example, I think Jane Campion is a phenomenal director, and Sofia Coppola as well, but they direct the sorts of films that people expect all female directors to do. It’s like, we already have them, and they’re great at what they do, so let’s see some female directors do different genres.

Exactly. No, precisely. In my case, it’s more the genre and the fact that I’m young in combination with being female. It’s because of those three things that I always have to work a little harder, you know?

Of course. And you mentioned not even letting yourself think about it, which seems smart. Like, it’s already affecting the way other people see you, so don’t let it affect the way you see yourself.

Yeah, totally. And like I said, when I looked at the questions from female students at these Q&As, I felt like they were doing just that.

At the same time, I think it’s fair to want to be prepared.

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, this was my personal choice—I didn’t want to let my gender encumber me any more than what was beyond my control. I was just like “I’m talented and I want direct movies,” versus “I’m female and I want to direct movies,” you know what I mean?

After.Life is in theatres now.

1 comment:

I really do want to see this movie! Great interview.

- Vanessa

http://peacejoystyle.wordpress.com

Post a Comment